It’s a clear sunny May morning at the Marina, California, airport with a gentle wind blowing in from the ocean. Just inside the open hangar doors of a tall, window-lined 1960s former helicopter hangar, a group of flight test engineers and support staff sit behind large computer screens. The test team, along with an array of data gathering antennas and cameras, face the far end of the airport. A Robinson R44 helicopter hovers over the grass by the runway, preparing to chase the aircraft starting up in the distance.

The object of all this attention, one of Joby Aviation’s demonstration and test aircraft, lifts from the tarmac and hovers to the threshold. As it turns onto the runway, its six propellers slowly rotate from horizontal to vertical orientation, gently propelling the aircraft forward as it gains altitude and completes its transition into forward flight. Flying alongside, the helicopter is quickly overtaken as the powered lift aircraft enters full forward flight, increasing speed to keep up.

The Joby aircraft made several circuits above the airport, as the test pilot provided a near constant stream of observations over the radio about the aircraft’s handling, the wind’s effect on it as it turned and changed speeds, and how the aircraft responded to flight control inputs.

One thing that couldn’t be observed by those on the ground, however, was the Joby’s low noise profile. Marketed as being as quiet as a conversation, the sound of the five-seat aircraft was indistinguishable over the R44 throughout the entire test flight. There was no question it was much quieter than the helicopter, a key goal to gain public acceptance and air taxi market share in urban areas.

Crawl. Walk. Run.

JoeBen Bevirt, who went by the name Joby in his childhood, founded Joby Aviation in 2009 to develop a sustainable, all-electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft. An engineer and successful entrepreneur, his previous ventures included one of the first full-suspension mountain bikes, a robotic laboratory system for life sciences discovery, the GorillaPod flexible camera tripod, and Joby Energy, which developed highly efficient, lightweight, brushless, permanent magnet motors and generators with high power density.

Initially funded by Bevirt from sales of his previous successful ventures, Joby Aviation was one of the first funded and backed eVTOL development companies — meaning just about every component required to create a successful aircraft didn’t yet exist, not to mention an FAA aircraft type, regulations, or infrastructure.

Undeterred and determined to blaze a new path, seven engineers worked together in a barn on Bevirt’s Santa Cruz ranch expanding new technologies such as electric motors, flight software, and lithium-ion batteries. This early work solidified how Joby would operate moving forward.

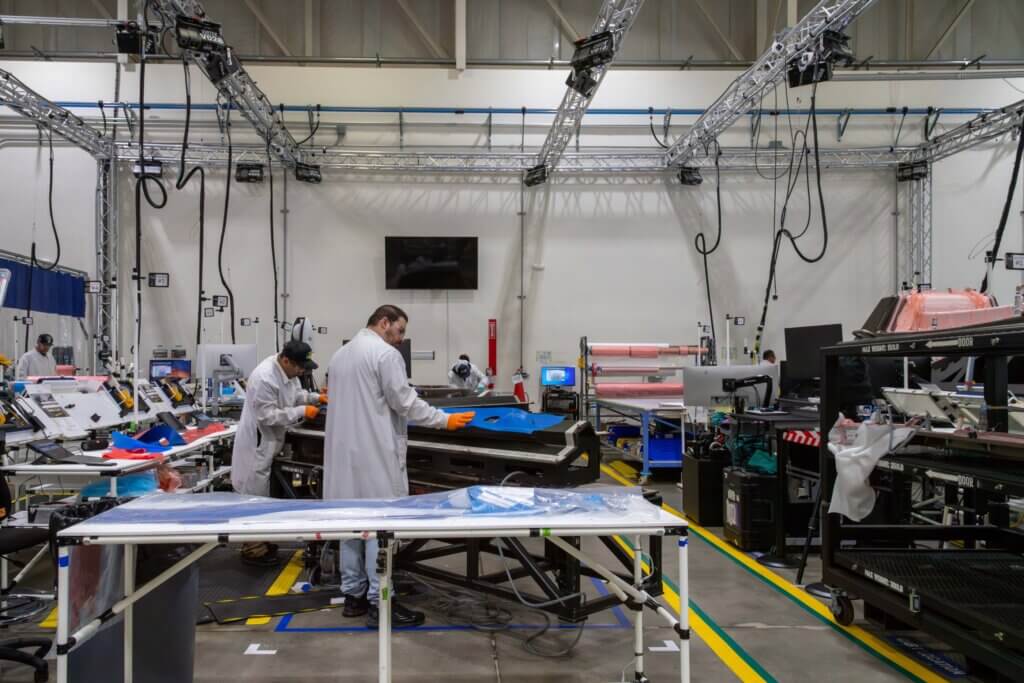

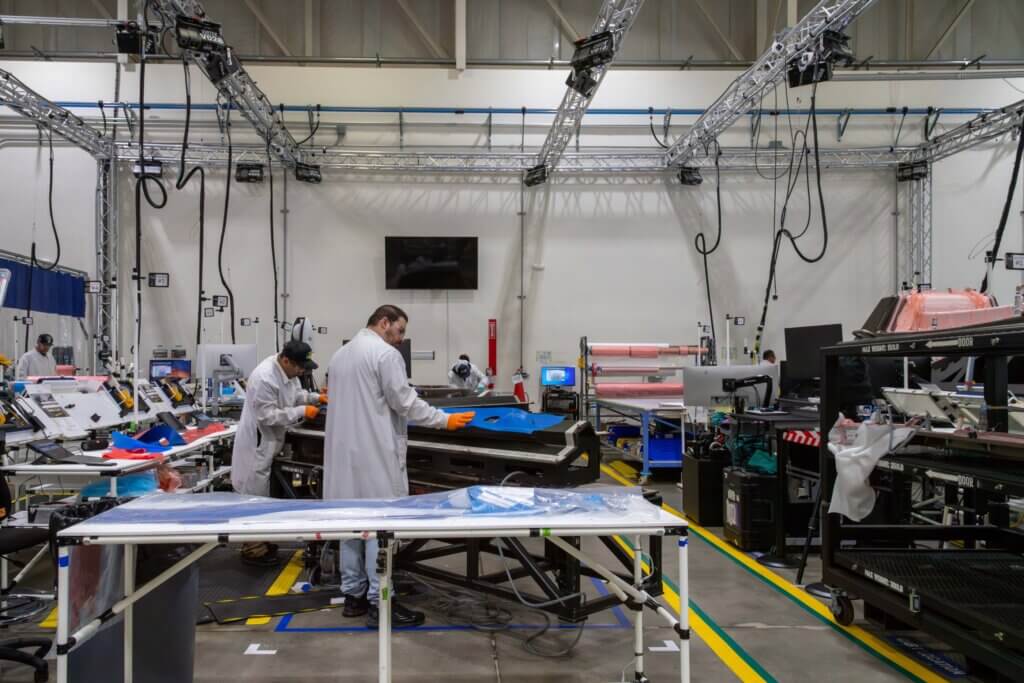

“As one of the first companies in this space, we realized early on that the components we needed to achieve the performance level we wanted didn’t exist,” Joby chief product officer Eric Allison explained during a tour of the company’s Marina facilities. “We either had to pay others to invent them or do it ourselves. So, we’ve taken the approach of vertically integrating our capabilities – building up to design, build, test, and certify all these different components to build our aircraft – which allows us to both move faster and be more nimble.”

Joby works with a few third-tier suppliers for things such as carbon fiber material, parts used to manufacture its electrical components, battery cells for its in-house battery modules, etc., then manufactures everything from motors, actuators, battery packs, and power electronics to propellers, airframe components, and skin.

Joby manufactures and tests its electronics, batteries, and motors at its San Carlos, California, facility, then ships them to Marina for assembly. In Marina, the company performs composites and airframe parts manufacturing and full aircraft assembly and testing.

The process of developing and certifying every part and component in house, designing and testing configurations, then adjusting and testing further, continued for six years before Joby settled on its current configuration – a four-passenger, single-pilot design. A subscale demonstrator was created in 2015. Two years later, a full-scale demonstrator took flight remotely, followed by a pre-production prototype in 2019 and the official beginning of the FAA type certification process — 10 years after the company formed.

A key part of Joby’s aircraft development is its integrated test lab. A technical mock-up of the aircraft’s systems, the lab uses the actual systems, motors, batteries, and components, all attached to a frame that simulates their location on the aircraft. A fixed-based simulator allows a pilot to “fly” the aircraft while the lab responds to the inputs in real time, allowing engineers to apply loads to the actual hardware that simulate flight and give them insight into how the aircraft will interact in real world scenarios. The lab has been invaluable in Joby’s crawl, walk, run philosophy, allowing the company to safely test components, limitations, scenarios, control design, and more, Allison said.

More than an aircraft

Joby’s vertical integration philosophy extends well beyond aircraft production. For the idea of a zero emission, quiet, sustainable air taxi service to really take off, Joby would need to develop a full service, from aircraft to execution.

“Joby has always had a vision of integrating the innovation of the aircraft with the service, in some ways harkening back to the beginning of aviation when United Airlines, Boeing, and Pratt & Whitney were all the same company before the Air Mail Act,” Allison said. “We started with an ethos of vertical integration on the hardware component side and developing the technology. As we’ve gotten closer to certification, we started also focusing on vertical integration to the customer and service as well.”

To achieve this, the company will ultimately provide aircraft development, production, air taxi service, infrastructure development, operations, and maintenance support. All of these steps require their own individual FAA authorizations.

Joby applied for its own FAA Part 135 certificate rather than buy one, allowing it to develop its operations from scratch with more than 1,000 pages of manuals. It received its Part 135 certificate in 2022 with a Cirrus 22 airplane, with plans to add the Joby aircraft once it receives type certification.

In 2024, it received its FAA Part 145 maintenance certificate, which was initially approved to allow Joby to perform select airframe, radio, and instrument repairs on traditional aircraft, again with plans to add the Joby aircraft once certified.

Simultaneously, Joby tackled the pilot training hurdle. With an entirely new aircraft type, which has only one pilot seat, a training program would need to be devised. Well before the FAA released its SFAR last October outlining pilot training and certification requirements for eVTOL, Joby was well down the certification road for a Part 141 training academy, which it received last December. Again, the certificate allows the company to train airplane pilots for now, with plans to add the Joby aircraft upon certification.

As a part of that training plan, Joby has partnered with CAE to develop full-motion six-axis level C flight simulators, which will be separately approved under FAA Part 60. When the simulators are certified and in place, Joby plans to obtain an FAA Part 142 training center designation, with the two training programs allowing it to quickly type-rate current airline pilots in the Joby aircraft in six weeks, while also providing airplane training for future Joby pilots — from private to flight instructor — through the Part 141 flight school.

“There is a lot of interest in flying the Joby; we already have a pretty long list of interested pilots,” Joby director of communications Oliver Walker-Jones said.

While the flight operations team worked on those certifications, another side of the company was preparing for airline operations. After previously receiving investment from and developing a partnership with Uber, Joby acquired Uber’s aerial ridesharing operations software and product, Uber Elevate, in 2020. Joby has since expanded the tool, integrating it with Joby’s full software operating system.

Born and raised in the tech industry, Joby developed a fully digital and integrated operations system to run its entire airline operation. This includes a fully electronic flight bag that not only tracks schedules and flight information, but also monitors pilot currency, training, and flight time. The system also features an operations core, a maintenance tracking and prediction platform, and a rider app. All components are written in the same language, function seamlessly together, and can integrate with third-party applications as needed — such as a customer’s reservations system.

The result was ElevateOS, which allows the company to achieve the level of on-demand, multi-modal trips it plans to deliver, while working behind the scenes with all other aspects of the system.

Joby has been testing the software as it provides flights in the Cirrus to employees and paying customers through its Part 135 operation, preparing it for full integration with the Joby aircraft.

Preparing for Launch

Initially, and in partnership with Delta Air Lines and Uber’s services, Joby will operate from select urban vertiports and at major airports once the aircraft is certified, with New York and Los Angeles planned as initial launch markets. With the addition of Joby’s service, an Uber customer can use the Uber app to order a trip from doorstep to doorstep, which could include a car ride to a vertiport, and a Joby ride between vertiports. Joby’s target pricing model is to eventually be able to provide the flight portion of the service at a rate comparable to UberX.

Simultaneously, Joby has also built a partnership with Virgin Atlantic in the U.K. It is also working with Dubai’s Road and Transport Authority in the United Arab Emirates. Joby will be the aircraft operator, providing air taxi service as an independent operator and, for partners like Delta, will integrate with the partner’s customer-facing channels for seamless booking. Testing operations in Dubai are expected to begin later this year with its service in New York planned to begin as soon as the aircraft is FAA type certificated, which Allison hopes is in 2026.

As for infrastructure, the New York Economic Development Corporation recently announced development of the Downtown Skyport, the site of the former Downtown Manhattan Heliport. The 34th Street Heliport is already undergoing conversion to handle electric air taxis. A vertiport in Dubai began construction last November in anticipation of service later this year.

Back home, Joby has already produced five production aircraft currently flying and is preparing for full production (about 25 aircraft a year to start) with a new 220,000-foot facility expected to be complete by mid-2025. The company purchased an existing facility in Dayton, Ohio, last year, which will begin manufacturing titanium and aluminum parts later this year.

The aircraft continues to fly daily as engineers test and refine systems. Recently it underwent extensive systems failure testing at Edwards Air Force Base.

The Joby is designed with triple redundancy across electronics to prevent a complete system failure. In the remotely piloted tests, engineers intentionally shut down components such as batteries, motors, and even tilt mechanisms to determine if the aircraft noticed and responded with redundancy protocols.

“We kept turning things off, and the aircraft kept reacting as it should,” Allison said. “We did this in simulation and in the lab, but we expected the pilot would have to respond in the real world, and what we learned is the pilot doesn’t have to do anything differently. You can complete the flight as normal. That gave us the confidence to move to routine pilot-on-board testing.”

Since the full-scale pre-production prototype’s first flight in 2017, the five aircraft in Joby’s fleet have flown well over 1,500 flights and more than 40,000 miles.

“You learn a lot from doing and flying the aircraft every day,” Allison added. “You learn about the way the components are performing. You learn about the right way to fly these aircraft.

“We’re happy to see so much investment overall in this [eVTOL] space. It’s becoming an industry, not just one company. At the same time, I think that maybe sometimes folks underestimate the value of those hard lessons that you must learn by doing, learning, repeating, and doing over and over again. We think we’re ahead of the pack when it comes to that, because we certainly have been building and flying for quite some time and are really focused on getting this technology right. When we put it in the hands of customers and start that service, it will be the way we envisioned.”

Joby Aircraft by the Numbers

Height: 11.3 feet (3.44 meters) when propellers in horizontal position / 13.76 feet (4.19 meters) when propellers in vertical position

Length: 21 feet (6.4 meters)

Width: 39 feet (11.88 meters)

Sound Level flying over at 1,640 feet (500 meters): 45 dBA

Sound level during take-off and landing (300 feet/100 meters): 65 dBA

Maximum distance on a single charge: 100 miles (160 kilometers)

Maximum speed: 200 mph (322 km/h)

Time to charge: The aircraft is designed to recharge enough for the next flight in the time it takes to unload and load passengers.

For comparison: A Robinson R44 is 38 feet long, with a 33-foot rotor diameter and stands 10.75 feet tall. A 45 dBA sound level is similar to that of a library or a quiet room, while 65 dBA is quieter than vacuum cleaners or traffic driving by.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(773x388:775x390)/kim-kardashian-graduates-law-school-2-052125-e46e2f81543a423c94c14519169a5271.jpg?w=100&resize=100,75&ssl=1)