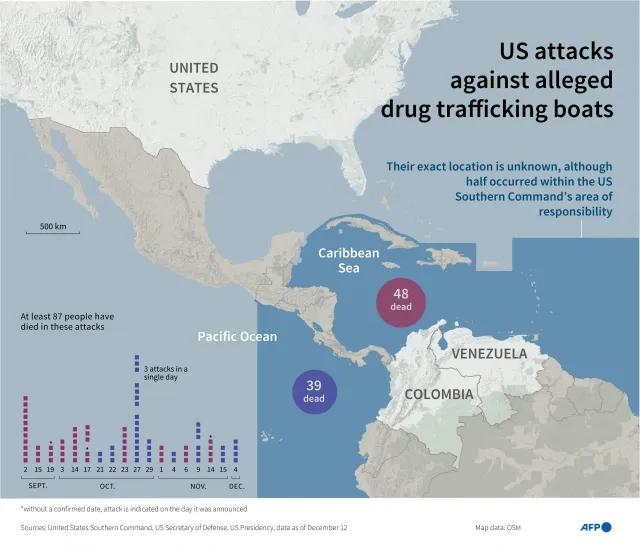

As the United States embarks on an unprecedented campaign of airstrikes in the waters of the Western Hemisphere and threatens to expand operations to Venezuela, those challenging the legality of the approach are set to face a tough path toward reining in the White House’s warpath.

Such challenges have come from a number of sources, including regional countries, a recent United Nations panel of experts, as well as U.S. lawmakers, some of whom are preparing to mount a battle in Congress. The legislative approach is rooted in an attempt to invoke the War Powers Resolution to prevent President Donald Trump’s administration from taking the fight against suspected drug traffickers in the Caribbean and Pacific Ocean to Venezuela, which the White House argues constitutes a major source of narcotics flowing into the U.S.

But former officials who have firsthand experience in advising the U.S. government on legal issues see few avenues to restrict the White House’s authority, and all of them are subject to considerable roadblocks.

The dilemma raises broader questions regarding the murky scope of military power afforded to the executive branch, particularly under an administration that has already removed a number of top military lawyers deemed unsuited to carry out its orders.

«The traditional answer has been a legal architecture that understands that the role of a government lawyer, particularly in the national security realm, is not to challenge authority, but to question it and we know what’s happened to them there,» Geoffrey Corn, a former U.S. Army senior law of war expert adviser now serving as director of Texas Tech University’s Center for Military Law & Policy, told Newsweek.

As a result, he argued, «the guardrails have been knocked down,» and «what’s left? the answer is one word: Congress,» where an attempt to invoke the War Powers Resolution would require lawmakers to muster up a successful majority vote and then assemble an even less likely two-thirds coalition to counter an inevitable presidential veto.

«In my view, the only geography that this administration cares about is Capitol Hill,» Corn said, «because if Congress is indifferent or tolerant to their assertions of these over-broad assertions of legal authority, they have nothing to worry about.»

It’s a situation where he said he recalls a centuries-old maxim attributed to French leader Napoleon Bonaparte: «The tools belong to the man who can use them.»

«And in my view, that’s what’s going on here,» Corn said. «As long as Congress tolerates the president using the tool of the military in, what I believe is, an overzealous manner, he’s going to continue to do it.»

The Power of War

Unlike Napoleon’s empire, the U.S. has in place a system of checks and balances to weigh authority between the executive, legislative and judicial branches. But this arrangement has been subject to perpetual debate since the nation’s founding 250 years ago, and the ambiguities of presidential power have been noted in previous rulings.

Among the most famous was the 1952 case Youngtown Sheet v. Sawyer, through which the Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional an attempt by then-President Harry Truman to seize steel industries in order to prevent a strike during the Korean War. In his landmark opinion, Justice Robert Jackson referenced the same words attributed to Napoleon, adding that he had «no illusion that any decision by this Court can keep power in the hands of Congress if it is not wise and timely in meeting its problems.»

Lawmakers sought to assert this power two decades later during another Cold War-era conflict, the war in Vietnam, when Congress enacted a rare override of then-President Richard Nixon’s veto to pass the War Powers Resolution in 1973 in response to the U.S. conducting a bombing campaign in neighboring Cambodia.

The resolution calls on the president to notify Congress within 48 hours of committing the U.S. military to conduct operations and outlines a 60-day window, after which further action would require explicit congressional approval. It’s been invoked many times over the decades, forcing successive presidents to submit around 130 reports pursuant to operations in Iraq, Somalia, Kosovo, Libya, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere.

Notably, however, the resolution has never once directly pushed the White House to withdraw troops or cease hostilities, and the 60-day deadline has usually been ignored, with the executive branch traditionally questioning the resolution’s capacity to introduce arbitrary limits to the very kind of presidential authority it recognizes.

«No president has ever conceded it’s constitutional, even when they issue reports that are within the scope of the War Powers Resolution, they will always refer to it as a report issued consistent with, not in accordance with,» Corn said. «Now, the real problem is it’s functionally unenforceable.

«First off, it acknowledges the president has authority to use military force to defend the nation against an attack, an emergency created by an attack,» Corn added. «All of this ties together. Why do you think the president has declared a national emergency related to the introduction of fentanyl? So, his lawyers can say, pursuant to Article Section One of the War Powers resolution, it says you have authority under the Constitution to use the armed forces to respond to an emergency created by an attack on the nation.»

Newsweek has reached out to the U.S. Department of War, Department of State and White House for comment.

Creative Interpretations

It’s not just Trump, Corn argued that «no president is going to agree» to the premise that the endorsement of 59 days of military action would be suddenly terminated on the 60th day.

Previous presidents, Democratic and Republican, have also found ways to circumvent the War Powers Resolution that may serve as a playbook for the current administration.

When the U.S. joined a NATO campaign of airstrikes in Libya in support of insurgents fighting to topple longtime ruler Muammar el-Qaddafi in 2011, the Department of Justice under then-President Barack Obama issued a memo defining «hostilities» as mentioned in the War Powers Resolution as explicitly meaning «war» as referenced in the Constitution.

Dakota Rudesill, associate professor of law at Ohio State University who has advisory experience in all three branches of government, explained that «there is no definition of ‘hostilities’ in the WPR statute, so DOJ has done that statutory interpretation work regarding ‘hostilities’ in a way that narrows the term and thereby gives the president room to operate outside the WPR.'»

«‘Hostilities’ as DOJ defined them excludes even months of violent airstrikes such as the U.S. carried out in Libya, meaning the 60-90 clock does not operate in DOJ’s opinion,» Rudesill told Newsweek. «A much more extensive military operation is necessary, DOJ says.»

Another strategy, known as the «second-in-time canon,» was employed by outgoing President Bill Clinton in 2000 following congressional blowback over the U.S. role in the NATO bombing campaign against Yugoslavia during the 1999 Kosovo war. This statutory interpretation pertains to appropriation laws that provide funding for military operations.

«Under the Second-in-Time Canon, a later statute may be interpreted to supersede an earlier one with which it arguably conflicts,» Rudesill said. «The later statute acts as an effective amendment to the first.»

In both cases, the original War Powers Resolution authors had sought to preempt such challenges through careful wording. Rudesill explained that the resolution specifically used the term «hostilities» rather than «war» in order to meet a much broader definition of military action, and it specifically states that «authorization for hostilities shall NOT be inferred from such a later funding bill.»

But while he felt that these Department of Justice actions «were legally weak,» he also pointed out that «Congress did not respond to those moves by amending the WPR to overturn the DOJ interpretations.»

«This again goes to the point that Congress needs to use its abundant constitutional powers for them to be meaningful, or the Executive Branch will have ample room to deploy overly aggressive legal interpretations and then do what it wants—because the Executive uniquely among the three branches holds ‘the sword,’ the ability to act in the real world,» Rudesill said.

«The problem gets even worse when the Executive Branch tries to evade review of its legal reasoning by keeping it secret, as the Trump Administration acknowledges it has done here,» he added.

Meanwhile, he said the War Powers Resolution represents one of four methods through which he said lawmakers could pursue a challenge to the administration’s operations, the other three being Congress passing funding conditions or statutory rules to limit or halt military action, declining to fund military operations or even refusing to pass other legislation until the strikes ceased.

But it all comes down to the same core problem.

«Each of these four paths are dependent on congressional will,» Rudesill said, «veto-proof majorities, simple majority votes, or resolute holdout swing votes, as the case may be.»

Symbolic Gestures

Just because the complexities of the debate are daunting does not mean it’s not a battle worth fighting in the view of those advocating for a dedicated response from Congress.

Brian Finucane, senior adviser at the International Crisis Group and former legal adviser to the U.S. State Department, argued that resolutions induced with respect to the War Powers Resolution remain «one of the best mechanisms for Congress to push back, including because they’re a kind of mechanism for members of the minority to actually force a vote.»

«It’s a way that Congress, hopefully in a bipartisan fashion, can express opposition to potential military action in Venezuela, as well as opposition to continued bombing at sea,» Finucane told Newsweek during a panel hosted by the ReThink Media organization. «And even if they are not acted in law, which seems like a real long shot, they can nonetheless send an important political signal.»

Also responding to Newsweek‘s question during the panel, John Walsh, director for drug policy and the Andes at the Washington Office on Latin America, added that «the congressional actions and the debate that they’re seeking to achieve interplays with public opinion.»

«I think in the case of Trump, in particular, there are crosscurrents and, who knows what’s in his mind, but I think there are significant portions of the MAGA base who would be concerned about another ‘forever war,’ and, in particular, that their candidate and their guy sort of launched this war of choice,» Walsh said.

«So, I think the public opinion piece is going to be important, and there’s already clear evidence that most Americans want nothing to do with a U.S. war in Venezuela,» he added. «So, I think that’s the interplay. And I think if a congressional debate really takes in and takes hold, and the administration is somehow forced to present more of its ideas on this, the weight of public opinion will only grow heavier.»

The debate over the sea campaign and threats to Venezuela is muddled by public outrage over a real drug crisis, even if its ties to Venezuela remain questionable.

Speaking at an event at the White House on Friday, Trump claimed that U.S. operations in the Caribbean and Pacific Ocean have «knocked out 96 percent of the drugs coming in by water,» and that «every one of those boats you see get shot down, you just saved 25,000 American lives.»

«And now we’re starting by land, and by land is a lot easier, and that’s going to start happening,» Trump said, «and we’re not going to have people destroying our youth, destroying our families.»

Walsh argued that «the Trump administration has looked to weaponize that grief and anger by converting it into a sort of license to kill in the Caribbean,» despite the fact that «there is no fentanyl coming from Venezuela or elsewhere in South America overall.»

The designation of drug-trafficking cartels, including the alleged state-sponsored Cartel of the Suns in Venezuela, as foreign terrorist designations has also raised legal questions, as has Trump’s stated use of the term «war» to refer to hostilities in the Caribbean.

«By far the majority view among legal scholars is that the strikes have no legal basis under domestic or international law,» Stephen Pomper, chief of policy at the International Crisis Group, who previously served in a number of official roles, including on the National Security Council and as legal adviser to the State Department, told Newsweek. «The president does not have the organic right to use force in self-defense against drug traffickers because trafficking drugs is not an armed attack. Nor has Congress given him the right to do so.»

«The argument that designating these groups as Foreign Terrorist Organizations somehow does the work of a congressional authorization is ridiculous,» Pomper said. «FTO designations result in financial and visa sanctions and have criminal law implications—they do not confer any authority to use military force.»

He, too, felt it was time for lawmakers to step up.

«Congress is the only institution that can check the executive’s war power. The most powerful way for it to do that would be to cut off funding for the operations in question,» Pomper said. «That seems very unlikely—getting a majority would be very hard, and getting a veto-proof majority even harder.

«Still, putting anti-strike legislation into play sends a useful signal and raises the political costs of the Caribbean operation,» he added. «And it is particularly notable when members of the president’s own party join in, as we are starting to see in the House. So, it’s well worth doing.»

Testing the Waters

Corn, the Texas Tech University professor and former U.S. Army legal adviser, brought up another factor that raises the stakes regarding Trump’s ongoing operations and openly declared intentions to expand them, one demonstrated by the recent «double tap» strike in which the U.S. twice attacked a single vessel in the Caribbean in an apparent effort to mitigate the chances of survival.

The incident, along with other strikes, has elicited condemnation from the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights and U.N. experts, as well as a number of regional countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, and Venezuela. But Washington’s traditional lack of compliance with international judicial entities, such as the International Criminal Court, and its powerful veto at the U.N., adds yet another layer of immunity to the president’s position.

«You’re not going to get a judicial intervention to stop the president. You’re not going to get anything from the international community, the U.N. Security Council can’t do anything, because we can veto any resolution that Russia or China proposes,» Corn said.

«This is politics and diplomacy meeting international law, and actually, I think this latest incident with the double tap on the boat, I think the administration has been watching it to—no pun intended—test the waters,» Corn said. «How much can we get away with with Congress?»

As the Pentagon faces calls for the release of footage of the operations, Corn references another, often overlooked piece of the debate that is playing out in Washington with life-and-death consequences in the shores of the Americas, and that’s the fact that at «the end of this chain is an American man or woman in uniform who has to pull a trigger and kill somebody or multiple people and live with that.»

«So few people in this country ever wear a uniform. I don’t think they really appreciate the moral weight that that puts on someone,» Corn said. «I believe that before our government demands—not asks but demands—that members in uniform kill other human beings, they are entitled to moral clarity.»

«And moral clarity is derived from legal clarity. And this lack of legal clarity, I think, creates moral uncertainty, and I think that’s heartbreaking,» he added. «I don’t think it’s fair, and I don’t think it’s right.»